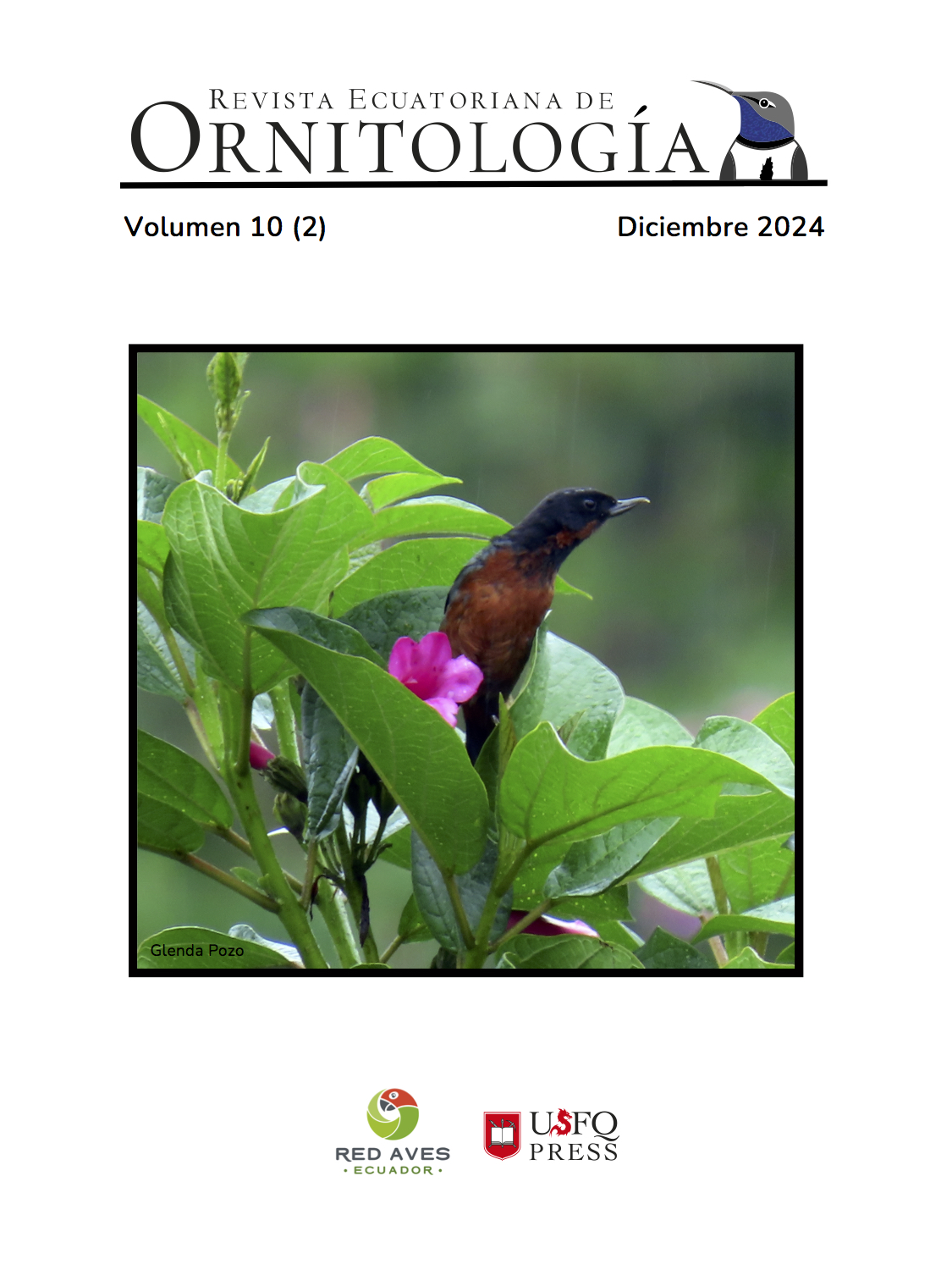

ACTIVE ANTING WITH A MILLIPEDE (DIPLOPODA) BY A TURQUOISE JAY Cyanolyca turcosa (CORVIDAE) IN THE SOUTHERN ANDES OF ECUADOR

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.18272/reo.v10i2.3092Palabras clave:

Azuay, comportamiento anti-parasitario, ectoparásitos, Parque Nacional Cajas, PasseriformesResumen

Algunos ectoparásitos de las aves pueden tener efectos adversos sobre la aptitud de su hospedador. Por lo tanto, comportamientos antiparasitarios como el “hormigueo” han evolucionado para combatirlos. En esta nota, presento un nuevo reporte de este comportamiento en la Urraca Turquesa Cyanolyca turcosa en el Parque Nacional Cajas, ubicado en los altos Andes del sur de Ecuador. Observé a un individuo de C. turcosa adulto utilizando un milpiés de tamaño medio para frotar activamente su plumaje, lo cual sugiere una estrategia de eliminación de parásitos externos (hormigueo). Tras 12 min de este comportamiento, el milpiés fue consumido por el ave. Esta observación abre la posibilidad de que este comportamiento sea más común de lo que se pensaba.

Descargas

Citas

Astudillo, P. X., Tinoco, B. A. & Siddons, D. C. (2015). The avifauna of Cajas National Park and Mazán Reserve, southern Ecuador, with notes on new records. Cotinga, 37, 1–11. URL: https://www.neotropicalbirdclub.org/cotinga/C37_online/Astudillo_et_al.pdf

Bush, S. E. & Clayton, D. H. (2018). Anti-parasite behaviour of birds. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 373(1751), 20170196. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0196

Clayton, D. H., Koop, J. A. H., Harbison, C. W., Moyer, B. B. & Bush, S. E. (2010). How birds combat ectoparasites. Open Ornithology Journal, 3, 41–71. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2174/1874453201003010041

Carroll, J., Kramer, M., Weldon, P. & Robbins, R. (2005). Anointing chemicals and ectoparasites: effects of benzoquinones from millipedes on the lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 31(1), 63e75. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-005-0974-4

Coulson, J. O. (2023). Turquoise jay (Cyanolyca turcosa) self-anointing (anting) with a millipede. Ornitología Neotropical, 34(1), 17–20. DOI: https://doi.org/10.58843/ornneo.v34i1.971

Enghoff, H., Golovatch, S., Short, M., Stoev, P. & Wesener, T. (2015). Diplopoda -taxonomic overview. In A. Minelli (Ed.), Treatise on zoology-anatomy, taxonomy, biology. The Myriapoda, vol. 2. (pp. 363–453). Brill.

Freile, J. & Restall, R. (2018). Birds of Ecuador. Helm Field Guides.

Hendricks, P. & Norment, G. (2015). Anting behavior by the northwestern crow (Corvus caurinus) and American crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos). Northwestern Naturalist, 96(2), 143–146. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1898/1051-1733-96.2.143

Hogue, C. L. (1993). Latin American insects and entomology. University of California Press. URL: https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_3CTf8bnlndwC

Hopla, C. E., Durden, L. A. & Keirans, J. E. (1994). Ectoparasites and classification. Revue Scientifique et Technique-Office International des Epizooties, 13(4), 985–034. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20506/rst.13.4.815

Lehmann, T. (1993). Ectoparasites: direct impact on host fitness. Parasitology Today, 9(1), 8–13. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-4758(93)90153-7

Møller, A. P. (1993). Ectoparasites increase the cost of reproduction in their hosts. Journal of Animal Ecology, 62(2) 309–322. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/3545368

Morozov, N. S. (2015). Why do birds practice anting? Biology Bulletin Reviews, 5, 353–365. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1134/S2079086415040076

Pérez-Rivera, R. A. (2019). Use of millipedes as food and for self-anointing by the Puerto Rican Grackle (Quiscalus niger brachypterus). Ornitología Neotropical, 30, 69–71. DOI: https://doi.org/10.58843/ornneo.v30i0.441

Potter, E. (1970). Anting in wild birds, its frequency and probable purpose. The Auk, 87(4), 692–713. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/4083703

Proctor, H. & Owens, I. (2000). Mites and birds: diversity, parasitism and coevolution. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 15(9), 358–364. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(00)01924-8

Shear, W. A. (2015). The chemical defenses of millipedes (Diplopoda): biochemistry, physiology and ecology. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology, 61, 78–117. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bse.2015.04.033

Simmons, K. E. L. (1957). A review of the anting-behaviour of passerine birds. British Birds, 50(10), 401–424. URL: https://eurekamag.com/research/029/774/029774654.php

Taylor, A. H. (2014). Corvid cognition. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 5(3), 361–372. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.1286

Weldon, P. J. & Carroll, J. F. (2006). Vertebrate chemical defense: secreted and topically acquired deterrents of arthropods. In M. Debboun, S. P. Frances & D. Strickman (Eds.), Insect repellents: principles, methods and uses (pp. 47–75). CRC Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420006650

Weldon, P. J., Aldrich, J. R., Klun, J. A., Oliver, J. E. & Debboun, M. (2003). Benzoquinones from millipedes deter mosquitoes and elicit self-anointing in capuchin monkeys (Cebus spp.). Naturwissenschaften, 90, 301–304. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-003-0427-2

Whiteman, N. K. & Parker, P. G. (2004). Effects of host sociality on ectoparasite population biology. Journal of Parasitology, 90(5), 939–947. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1645/GE-310R

Descargas

Publicado

Cómo citar

Número

Sección

Licencia

Derechos de autor 2024 Pablo Sebastián Padron

Esta obra está bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 4.0.

Los autores que publiquen en la Revista Ecuatoriana de Ornitología aceptan los siguientes términos:

- Los autores/as conservarán sus derechos de autor y garantizarán a la revista el derecho de primera publicación de su obra, el cuál estará simultáneamente sujeto a la Licencia de Reconocimiento No Comercial de Creative Commons.

- Los autores/as podrán adoptar otros acuerdos de licencia no exclusiva de distribución de la versión de la obra publicada, pudiendo de esa forma publicarla en un volumen monográfico o reproducirla de otras formas, siempre que se indique la publicación inicial en esta revista.

- Se permite y se recomienda a los autores difundir su obra a través de Internet en su repositorio institucional, página web personal, o red social científica (como ResearchGate o Academia.edu).