Immigrant Gnosis: Hacer obra en los Estados Unidos

post(s)

Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Ecuador

Recepción: 28 Septiembre 2021

Aprobación: 14 Octubre 2021

Cómo citar: Alvarez, A. (2021). Immigrant Gnosis: Hacer obra en los Estados Unidos. En post(s), volumen 7 (pp. 180-207). Quito: USFQ PRESS.

Resumen: Este ensayo propone una reflexión sobre el trabajo curatorial que realicé para la exhibición Comunidades visibles: La materialidad de la migración, expuesta entre febrero y mayo de 2021, en el Albright-Knox Art Gallery, en Buffalo, Nueva York. La propuesta reunió la obra de ocho artistas latinx que son inmigrantes de primera o segunda generación. En sus prácticas creativas, los artistas celebran sus comunidades. Cada artista combina materiales y técnicas de su país de origen, de otros lugares colonizados, o de su contexto presente, con referencias cotidianas o tomadas de la historia del arte.

Palabras clave: latinx, migración, comunidades, historia, arte contemporáneo.

Abstract: This essay proposes a reflection on the curatorial work I did for the exhibition Comunidades Visibles: The Materiality of Migration, exhibited between February and May 2021, at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, in Buffalo, New York. The exhibition brought together artworks by first- or second-generation immigrant Latinx artists. Each combines materials and techniques from their country of origin, from other colonized places, or from their present context with everyday or art historical references.

Keywords: latinx, migration, communities, history, contemporary art.

(English version)

A recent exhibition, Comunidades Visibles: The Materiality of Migration, held at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York from February to May 2021 highlighted the contributions of first- and second-generation Latinx immigrant artists who celebrate their personal and communities' histories while also interrogating the stories that form their foundations [fig. 1], Each combines materials and techniques from their country of origin, other colonized places, and their present contexts as they transform sometimes difficult narratives into art that conveys urgent and consequential stories about historical and contemporary immigration. These artists—Carolina Aranibar-Fernández (Bolivian, born 1990), Esperanza Cortés (Colombian, born 1957), Raúl de Nieves (Mexican, born 1983), Patrick Martinez (American, born 1980), Ronny Quevedo (Ecuadorian, born 1981), and Felipe Shibuya (Brazilian, born 1986)—are firstand second-generation immigrants to the United States. I gathered this group of artists and curated this exhibition in response to my own experiences as an Ecuadorian immigrant to the United States. As individuals who have traversed national borders for permanent relocation, or whose parents have done so, we are all intimately familiar with the bureaucratic, punitive, and dangerous liminality that exists at this nation's physical borders.

When one passes through a national border in the pursuit of a new home, they are invisibly and indelibly marked by the experience. Scholar Walter D. Mignolo (2012) has coined the term border gnosisto referto a kind of knowledge that comes from dwelling in imperial and colonial borderlands. Expanding upon this notion, I have observed that bearing the mark of passage as an immigrant into the United States is its own kind of knowledge. The psychological, emotional, and cultural remnants of this shared experience contribute to all aspects of life for U.S. immigrants. Among other things, this leads to the formation of communities that are united by their destabilized definition of "home" and urgent need to assimilate. The artworks exhibited in Comunidades Visibles are informed by this immigrant gnosis, the knowledge that comes from inhabiting an "immigrant" identity in the United States. Furthermore, my work as a curator and, more broadly, experiences in the art world are informed by my own immigrant gnosis.

An executive memorandum issued on July 21, 2020 by the office of the 45th President of the United States of America directed that some immigrant groups, including undocumented Americans and refugees, be excluded from the population count used to apportion congressional representation following the 2020 census, rather than using "the whole number of persons" mandated by the Constitution.[1] The presidential guidance was challenged by multiple states in the United States Supreme Court and was heeded by the Census Bureau until January 12, 2021. While the feasibility of its execution was questionable from the outset, the policy had detrimental effects on the enumeration process, as it discouraged participation by vulnerable people who should have been counted. This blatant effort to render immigrant populations invisible joins a long legacy of similar practices in this and other nations. The marginalization and erasure of minoritized groups is an imperialist strategy devised to uphold existing class structures and reinforce power dynamics. In the face of these gestures, immigrant communities continue to exist—even thrive—thanks in large parttothe persistent advocacy and attention of artists, writers, and activists.

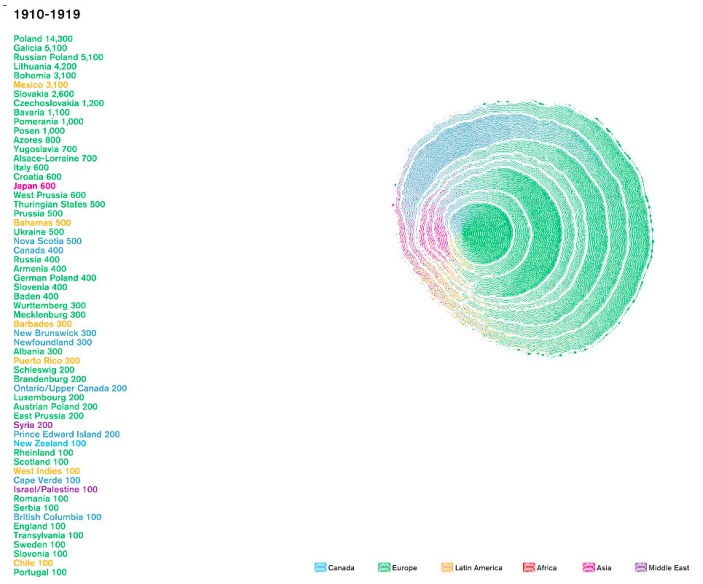

Visibility is vitally important to social groups, as it allows them to occupy space, claim political and collective power, and assert cultural relevance. Pedro M. Cruz, Felipe Shibuya, and John Wihbey’s data visualization in Dendrochronology of Immigrants and Natural-borns in the US is an important gesture to this effect [fig. 2]. When Shibuya and Cruz immigrated to the United States in 2016, they were faced with tremendous amounts of anti-immigrant rhetoric. They created this work as they sought to understand and articulate their membership in a widespread and intergenerational community of immigrants, all of whom are integral to the country’s economic and cultural development. Accompanied by ambient forest sounds, the visualization video shows a crosssection of a digitally rendered tree that grows as immigrants, represented by cells on the tree rings, who arrive to create new rings, as well as a list of dates and countries of origin that scroll by on the left. In transforming decades of census data into an image of a growing tree, the work underscores the fact that migration is a natural phenomenon—one that occurs among many plant and animal species as well as among humans.

Figure 2.

Felipe Shibuya, Dendrochronology of Immigrants and Natural-borns in the US, Collaborative work with Pedro M. Cruz, John Wihbey, and Avni Ghael (Northeastern University), 2018. Video. © Felipe Shibuya. Video still courtesy of the artist.

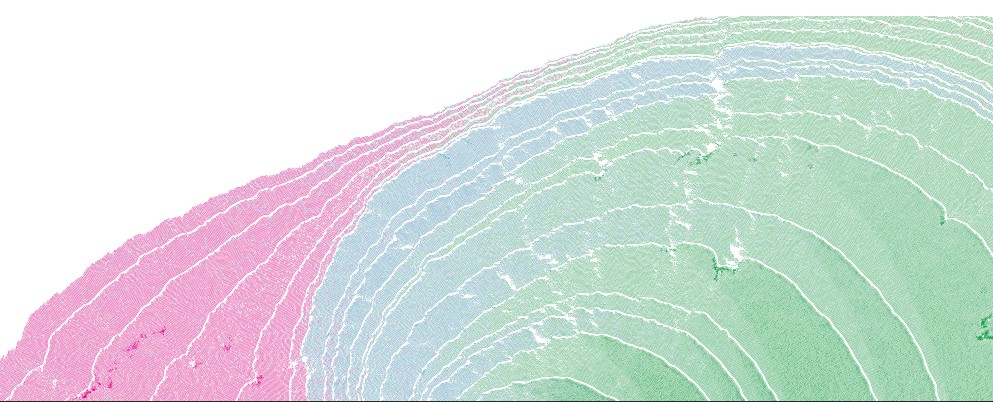

This video and the accompanying prints like Dendrochronology of United States Immigration, New York State detail [fig. 3] also illustrate the degree to which this country’s history is contingent on a tremendous amount of immigration. The inherent diversity of this country, founded as it was upon colonialization and displacement of native people, is often strategically forgotten when members of the white, European-descended majority seek to cease or impede contemporary immigration. This body of work by Cruz, Shibuya, and Wihbey serves as a reminder to those whose ancestors immigrated long ago that they are part of the history of immigration in this country, even though they do not have the immigrant gnosis shared by those of us who have personally experienced permanent migration. The prints that accompany the video in the exhibition, one of New York State and the other of the United States, highlight the true demographic makeup of these regions. The true diversity of these places is easily forgotten, especially in communities that are still shaped by histories of segregation and redlining, the systemic, discriminatory denial of economic opportunities in neighborhoods based on their racial demographics.

Figure 3.

Detail. Pedro M. Cruz, Felipe Shibuya, and John Wihbey. Dendrochronology of United States Immigration, New York State detail, 2018. Exhibition print. © Felipe Shibuya. Image courtesy of the artist.

Motivation for immigration to the United States is often attributed to economic striving or a desire to achieve the "American Dream." What is often forgotten or downplayed is the degree to which some migrations were and are reluctant or even forced. Carolina Aranibar-Fernández's Desplazamiento y Subsuelo (Displacement and Subsoil) [fig. 4] brings this issue to the fore. Atop a flowery lace map of the world made from pieces of embroidered Bolivian mantas, or shawls, the artist has sewn extraction lines and trade routes using glass beads. These delicate delineations trace the transport of goods and people in the service of empire-building and colonialist expansion, including the movement of enslaved people and natural resources like petroleum, gold, and silver. In many cases, the extraction of these resources has enriched international corporations and governments while contributing to the economic, political, and social instability of the depleted regions. In turn, people who inhabitthese regions are forced to emigrate and seek opportunities and stability elsewhere.

Figure 4.

Installation view of Carolina Aranibar-Fernández's Desplazamiento y Subsuelo (Displacement and Subsoil), 2020-2021, in Comunidades Visibles: The Materiality of Migration (February 12-May 16, 2021, Albright-Knox Northland, Buffalo, New York). Artwork Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York; Charlotte A. Watson Fund, by exchange, 2021 (2021:3a-d). © Carolina Aranibar- Fernández. Photograph by Brenda Bieger and Amanda Smith.

This history is also laid bare in Esperanza Cortés's Empire, which features over 1,000 feet of gold chains and glass beads cascading down from a gold chandelier that hangs nearly 20 feet above a red velvet platform [fig. 5]. The work evokes the extraction of gold from Latin America in support of the Spanish empire, which decimated the economic growth potential of various nations and continues to affect the region. Both of these artworks show the way that Aranibar-Fernández and Cortés keep colonialist and imperialist histories at the forefront of their minds. As artists who immigrated into the United States but who maintain strong ties to their home countries —Bolivia and Colombia, respectively— they are compelled to explore the relationships between these nations and the global history of expansionism, especially as its legacy continues to affect marginalized populations.

Figure 5.

Installation view of Esperanza Cortés's Empire, 2017, in Comunidades Visibles: The Materiality of Migration (February 12-May 16, 2021, Albright-Knox Northland, Buffalo, New York). © Esperanza Cortés. Photograph by Brenda Bieger and Amanda Smith.

As is the case for all the artists in this exhibition, the material choices made by Aranibar-Fernández and Cortés were deliberate: the glass beads Aranibar-Fernández threaded into lines carry a similar meaning to those found in Cortés's work. For centuries, these beads were valued as currency and sometimes used as payment for labor. In both artists' practices, they also signify the exploitation of South and Central America, the Caribbean, and other colonized places around the world. Despite this legacy, glass beads have also come to carry a protective significance in the present day, a function that is important to both artists' work.

Just as Cruz, Shibuya, and Wihbey assert a strong connection between immigration and nature in their tree visualization, Aranibar-Fernández's floral lace map is a commentary on the relationship between humans and the natural world. Despite humans' exploitation of land and nature as a source of profit and opportunity for the expansion of power, the propagation of flowers remains a natural process. Aranibar-Fernández views the ways in which flowers bloom for their own procreative benefit, exceeding human desires, as an aesthetically appealing act of resistance to Western hegemonic structures. In her practice, she considers the commodification of not only land but also the human body. The privatization of land and politicization of borders have a damaging effect on the environment in the same way that the commodification of the human body—in the immigration carceral system among many other sectors—has tremendously deleterious effects. Aranibar-Fernández conjures the bodies of detained immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers through her use of emergency blankets that hang behind the map in Desplazamiento y Subsuelo. These blankets are distributed at often-underheated U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention centers. Widely circulated images of children wrapped in these inadequately warm sheets have exposed the inhumane conditions of such sites. Her use of this material is intended to remind us of those bodies—those humans—whose current subjection to unjust conditions is just the most recent horror in a long history of displacement initiated by colonialism and imperialism.

The body in motion is also of interest to Cortés, who spent much of her life as an Afro-Latin dancer. Today, her art incorporates embroidery carefully extracted from the dresses and shawls she wore before a 2014 bus accident ended her dance career. In Cradle and La Cordobesa [figs. 6, 7], Cortés adorns historical furniture with these textiles, layering their original meanings with hybrid associations addressing the diversification of the Americas. The empty cradle makes reference to the humanitarian crisis at the Southern border, specifically the more than 5,000 children separated from their parents there since July 2017.[2] By covering the cradle with protective glass beads and ornate floral embroidery that references the exploited natural world, Cortés highlights the complex colonialist project that has shaped the Americas into the present day while also conjuring a protective energy for the many children missing from their family homes.

Figure 6.

Installation view of Esperanza Cortés's Cradle, 2020, in Comunidades Visibles: The Materiality of Migration (February 12-May 16, 2021, Al brig ht-Knox Northland, Buffalo, New York). © Esperanza Cortés. Photograph by Brenda Bieger and Amanda Smith.

Figure 7.

Esperanza Cortés, La Cordobesa, 2016-2017. Personal embroidery, glass beads, glass pieces, Upper chair 20th century, chair legs 18th century; 42 x 20 x 26 inches (106.68 x 50.8 x 66.04 cm). © Esperanza Cortés. Image courtesy of the artist.

Figure 8.

Installation view of Raul De Nieves's Crown Me With Your Iron and Aid Me In My Fight, This and All of My Days, 2020, Celebratory Skin / Perseverence, 2019, and I woke up from a dream that gave me wings, 2020, in Comunidades Visibles: The Materiality of Migration (February 12-May 16, 2021, Albright-Knox Northland, Buffalo, New York). © Raul De Nieves. Photograph by Brenda Bieger and Amanda Smith.

Whereas Cortés's artwork contains elements that she used to wear, Raúl de Nieves creates elaborate costumes that he often enlivens through collaborative music and dance performances. The ensembles are densely layered with beads, feathers, and sequins. De Nieves draws inspiration for his use of beadwork from his Mexican heritage, and his costumes and faux stained-glass windows are replete with imagery alluding to Mexican traditions, world religions, mythology, and more. For example, the many frogs in Crown Me With Your Iron and Aid Me In My Fight, This and All of My Days [fig. 8] symbolize fertility, transformation, and growth, all of which are also evoked by the embryo in the top panel. Here, de Nieves explores themes of identity and self-realization through metaphors that conjure an ongoing project of transformation and healing. The fixed meanings, like growth, of the images in the window become unfixed and subjective as viewers with different backgrounds and experiences encounter the work. Importantly, de Nieves layers related imagery in order to enrich and heighten his message, which corresponds to how we ourselves are enriched through contact with others: an especially profound sentiment following a year marked by pandemic isolation and xenophobic policies.

Themes of self-definition, storytelling, and familial inheritance abound in Ronny Quevedo's work as well. Quevedo's practice is directly influenced by both of his parents' professions. His mother, a seamstress and dressmaker, has even helped him create several recent artworks, including topografia lyr(ic)a [fig. 9], In his choice of materials—thread, wax pattern paper, and muslin—he alludes to her labor and their relationship of inherited knowledge. Similarly, his interest in sports, especially soccer, basketball, and Ullamaliztli (the pre-Columbian ballgame considered the antecedent to various contemporary team sports), stems from his father's influence. Quevedo's father was a professional soccer player in Ecuador, and when the family moved to the United States, he worked as a referee and joined a local amateur soccer league. Migrant families from Central and South America and the Caribbean largely make up and coordinate these leagues which are found throughout the United States. The weekly convening of these individuals—who, despite arriving from different places, shared a language and the experience of assimilating to life in the United States—came to carry a ritualistic significance for Quevedo. The teams often played indoors on basketball courts originally built for schools or private groups, revealing, for the artist, the way that sites can be repurposed and reinvented for new functions. At a young age, Quevedo witnessed his father and their community stepping into a space that was not built for them and writing their own rules for its usage. Now, he views this as a metaphor for immigration and, especially, to celebrate the adaptability and resiliency of those with immigrant gnosis.

In the killing floor (making ground) [fig. 10], Quevedo layers references to historical and contemporary sports: a gymnasium floor marked with lines for basketball is rearranged to evoke the "I" formation of fields used for Ullamaliztli. Additional lines are newly drawn to further destabilize the link between this visual vocabulary and a particular sport. Metal armatures placed at either end recall soccer or American football goal posts, but here instead hold his drawings on muslin. Above, decagonal structures evocative of the stone hoops used in Ullamaliztli are made from plastic milk crates like those that often serve as basketball hoops in the Bronx, where Quevedo has lived since emigrating from Ecuador.

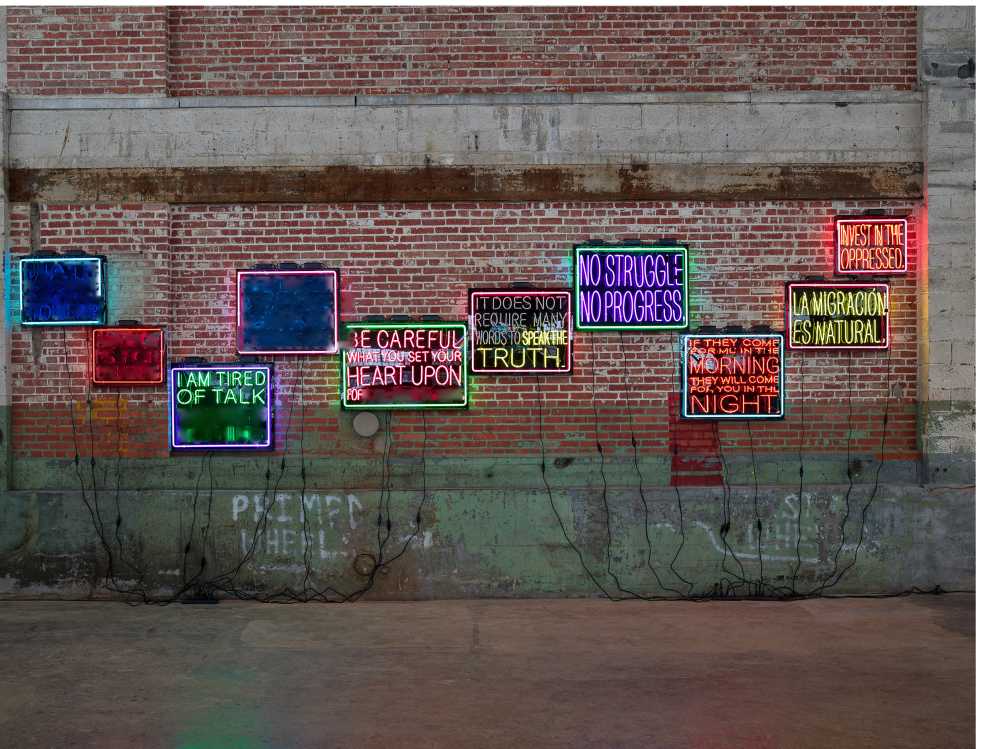

Quevedo's aesthetic is shaped by his current context in much the same way as that of Patrick Martinez. A Los Angeles-based artist, Martinez embraces spray paint, erasure, and the rough-hewn layered textures of urban materials to make work that recalls the cityscape and honors the stories told by its walls. This practice celebrating the surfaces of his hometown also evokes its history and complex cultural developments. Juxtaposition plays an important role in this body of work, as it does in the collage of neon signs created for this exhibition. Here Martinez groups ten discrete artworks featuring quotes, poems, and calls to action that invoke the words of immigration justice advocates and remind viewers that "immigration is natural," that "America is for Dreamers," and that "hate is too great a burden to bear" [fig. 11], Martinez often quotes historical figures who fought for racial and social justice, carrying their sentiments into the present stage of the ongoing struggle for equality across this nation. These signs deploy the visual language of commercial signage—an accessible, ubiquitous, and usually neutral medium —but subvert expectations by communicating unmistakably political messages.

Figure 11.

Installation view of artworks by Patrick Martinez in Comunidades Visibles: The Materiality of Migration (February 12-May 16, 2021, Albright-Knox Northland, Buffalo, New York). © Patrick Martinez. Photograph by Brenda Bieger and Amanda Smith.

In each project included in Comunidades Visibles: The Materiality of Migration, artists layer references from historical and contemporary sources, from different parts of the world, and from varied cultures in order to make work that speaks to their sensibilities as makers deeply in touch with their immigrant gnosis. The hybridity of the artworks corresponds closely to the hybrid identities of their makers—these material, natural, and human histories are inexorably intertwined and complex. Honoring their families and the stories that have shaped their lives, they celebrate and make visible the multiple communities to which they belong. In doing so, they demand acknowledgement of the inherent value of immigrant communities and communities of color, building on the enduring legacy of the artists and activists who came before them. I add my voice to these calls for justice, equity, and recognition; by organizing this exhibition in an internationally recognized art museum, my ambition was to provide a platform to amplify these artists' creative voices. While working closely with each artist on this project, I grew to appreciate the complexity of their relationships with this country and their heritage, which is not dissimilar to my own. The embodied experience of being an immigrant in the U.S. shapes our perceptions of recent political and social events, our responses to overt injustices like the census memorandum, and our creative outputs. It was through working with this group that I came to understand exactly how much we have in common as first- and second-generation immigrants and how I can and will use my role as an advocate for artists and Latinx people to increase our visibility in our (new) country. post(s)

(Versión en español)

Entre febrero y mayo de 2021, en el Albright-Knox Art Gallery, en Buffalo, Nueva York, se presentó la exposición Comunidades visibles: La materialidad de la migración. La muestra se concentró en destacar las contribuciones de artistas latinxs inmigrantes de primera y segunda generación, que celebran sus historias personales y de sus comunidades, al tiempo que cuestionan los relatos que conforman sus narrativas originarias [fig. 1], Cada artista combina materiales y técnicas de su país de origen, de otros lugares colonizados y de sus contextos actuales, mientras transforman narrativas particularmente difíciles en obras de arte que transmiten historias urgentes sobre la inmigración histórica y contemporánea.

Los artistas que participaron en la exhibición fueron Carolina Aranibar-Fernández (Bolivia, 1990), Esperanza Cortés (Colombia, 1957), Raúl de Nieves (México, 1983), Patrick Martínez (Estados Unidos, 1980), Ronny Quevedo (Ecuador, 1981) y Felipe Shibuya (Brasil, 1986). Junté a este grupo de artistas y realicé la curaduría de esta exhibición como respuesta a mis propias experiencias como ecuatoriana migrante en los Estados Unidos. Nuestros padres y madres o nosotrxs mismxs hemos atravesado distintas fronteras nacionales para reubicarnos de forma permanente y estamos íntimamente familiarizadxs con la burocrática, punitiva, y peligrosa liminal¡dad que existe en las fronteras físicas de este país.

La experiencia de atravesar una frontera nacional en busca de un nuevo hogar genera marcas invisibles e indelebles. El académico Walter D. Mignolo (2012) acuñó el término "gnosis fronteriza" para referirse a un tipo de conocimiento que proviene de habitar en tierras fronterizas imperiales y coloniales. Ampliando esta noción, he observado que llevar la marca de paso como inmigrante a los Estados Unidos produce un tipo de conocimiento en sí. Los rezagos psicológicos, emocionales y culturales de esta experiencia compartida contribuyen a la formación de comunidades que están unidas por su desestabilizada definición de 'hogar' y por la urgente necesidad de asimilación. Las obras de arte expuestas en Comunidades Visibles están conformadas por esta gnosis inmigrante, por el conocimiento que proviene de habitar una identidad 'inmigrante' en los Estados Unidos. Es más, mi propio trabajo como curadora y mis experiencias en el mundo del arte, de forma más amplia, están determinadas por mi propia 'gnosis inmigrante'.

Después del censo de 2020, un memorando ejecutivo emitido el 21 de julio de 2020 por la oficina del Presidente 45° de los Estados Unidos de América ordenó que se excluyera a algunos grupos de inmigrantes, incluidos los estadounidenses indocumentados y los refugiados, del recuento de población utilizado para distribuir los escaños de representación en el Congreso. Este memorando desafió a la Constitución, que establece que se debe contabilizar"el número total de personas".[1] La orden presidencial fue impugnada por varios estados en la Corte Suprema de los Estados Unidos y fue aplicada por la Oficina del Censo hasta el 12 de enero de 2021. Si bien la viabilidad de su ejecución fue cuestionada desde el principio, la política tuvo efectos perjudiciales en el proceso de conteo, ya que desalentó la participación de personas vulnerables que deberían haber sido contabilizadas.

Este esfuerzo flagrante por invisibilizar a las poblaciones de inmigrantes se suma a un largo legado de prácticas similares en esta y otras naciones. La marginación y eliminación de los grupos minoritarios es una estrategia imperialista ideada para mantener las estructuras de clase existentes y reforzar las dinámicas de poder. Sin embargo, pese a estos gestos, las comunidades de inmigrantes continúan existiendo, incluso prosperando, en gran parte gracias a la persistente defensa y atención de artistas, escritores y activistas.

La visibilidad es de vital importancia para los grupos sociales, ya que permite ocupar espacios, reclamar el poder político y colectivo, y afirmar su relevancia cultural. La visualización de datos de la obra Dendrocronología de inmigrantes y nacidos naturales en los Estados Unidos [fig. 2], de Pedro M. Cruz, Felipe Shibuya y John Wihbey, es un gesto importante en este sentido. Cuando Shibuya y Cruz emigraron a Estados Unidos en 2016, se enfrentaron a enormes cantidades de retórica antiinmigrante. Crearon este trabajo mientras buscaban comprender y articular su participación en una comunidad de inmigrantes amplia e intergeneracional, formada por personas que son parte integral del desarrollo económico y cultural del país. Acompañado por sonidos ambientales del bosque, el video muestra una sección transversal de un árbol renderizado digitalmente, que crece a medida que los inmigrantes, representados por células en los anillos de los árboles, llegan para crear nuevos anillos. A la izquierda de la pantalla se despliega una lista de fechas y países de origen. Al transformar décadas de datos del Censo en una imagen de un árbol en crecimiento, la obra subraya el hecho de que la migración es un fenómeno natural, que ocurre entre muchas especies de plantas y animales, así como entre los humanos.

Este video y las impresiones adicionales, como Dendrocronología de la inmigración de los Estados Unidos, detalle del estado de Nueva York [fig. 3], ilustran el grado en que la historia de este país depende de una enorme cantidad de inmigración. La diversidad inherente de este país, fundada sobre la colonización y el desplazamiento de las personas nativas, a menudo se olvida estratégicamente cuando los miembros de la mayoría blanca, descendiente de europeos, buscan detener o impedir la inmigración contemporánea. Este cuerpo de trabajo de Cruz, Shibuya y Wihbey sirve como un recordatorio para aquellos cuyos antepasados emigraron hace mucho tiempo y que son parte de la historia de la inmigración en este país, a pesar de que no tienen la gnosis inmigrante compartida por aquellos de nosotros que hemos experimentado personalmente la migración permanente. Los grabados que acompañaron al video en la exposición, uno del estado de Nueva York y el otro de Estados Unidos, resaltan la composición demográfica de estas regiones. La profunda diversidad de estos lugares se olvida fácilmente, especialmente en comunidades que todavía están moldeadas por historias de segregación y líneas rojas que no se cruzan, por la negación sistemática y discriminatoria de oportunidades económicas en los vecindarios, basada en función de su demografía racial.

La motivación para inmigrar a los Estados Unidos a menudo se atribuye al bienestar económico o al deseo de lograr el 'sueño americano'. Lo que a menudo se olvida, o se minimiza, es que algunas migraciones fueron y son reluctantes o incluso forzadas. Desplazamiento y Subsuelo (Displacement and Subsoil), de la artista Carolina Aranibar-Fernández [fig. 4], pone ese tema en primer plano. Sobre un mapa del mundo de encaje florido hecho con piezas de mantas o chales bolivianos bordados, la artista cosió líneas de extracción y rutas comerciales con cuentas de vidrio. Estas delicadas delineaciones trazan el transporte de mercancías y personas al servicio de la construcción del imperio y la expansión colonialista. Incluyen el movimiento de personas esclavizadas y de recursos naturales como el petróleo, el oro y la plata. En muchos casos, la extracción de estos recursos ha enriquecido a las corporaciones y gobiernos internacionales, al tiempo que ha contribuido a la inestabilidad económica, política y social de las regiones empobrecidas. A su vez, las personas que habitan estas regiones se ven obligadas a emigrar y buscar oportunidades y estabilidad en otros lugares.

Esta historia también queda al descubierto en la obra Imperio, de Esperanza Cortés, que está hecha con más de 300 metros de cadenas de oro y cuentas de vidrio, que caen en cascada desde un candelabro de oro que cuelga a casi seis metros de altura por encima de una plataforma de terciopelo rojo [fig. 5]. Este trabajo evoca la extracción de oro de América Latina, para apoyar al imperio español, que diezmó el potencial de crecimiento económico de varias naciones y aún sigue afectando a la región. Ambas obras de arte muestran la forma en que Aranibar-Fernández y Cortés mantienen las historias colonialistas e imperialistas presentes en sus mentes. Como artistas que inmigraron a los Estados Unidos pero que mantienen fuertes lazos con sus países de origen —Bolivia y Colombia, respectivamente—, se ven llamadas a explorar las relaciones entre estas naciones y la historia global del expansionismo, especialmente porque su legado continúa afectando a las poblaciones marginadas.

Como sucede con todos los artistas de esta exposición, la elección de materiales hecha por Aranibar-Fernández y Cortés fue deliberada: las cuentas de vidrio enhebradas en líneas de Aranibar-Fernández tienen un significado similar a las que se encuentran en la obra de Cortés. Durante siglos, estas cuentas se valoraban como moneda y, a veces, se usaban como pago por el trabajo. En las prácticas de ambas artistas, las cuentas también simbolizan la explotación de América del Sur y Central, el Caribe y otros lugares colonizados alrededor del mundo. A pesar de este legado, las perlas de vidrio también han llegado a tener un significado de protectoras en la actualidad, una función que es importante para el trabajo de las dos artistas.

Así como Cruz, Shibuya y Wihbey tienen una conexión profunda entre la inmigración y la naturaleza en su visualización de árboles, el mapa de encaje floral de Aranibar-Fernández es un comentario sobre la relación entre los humanos y el mundo natural. A pesar de la explotación de la tierra y la naturaleza como fuente de ganancias y oportunidad para la expansión del poder, la propagación de flores sigue siendo un proceso natural. Aranibar-Fernández ve las formas en que las flores florecen para su propio beneficio procreador, superando los deseos humanos, como un acto de resistencia estéticamente atractivo hacia las estructuras hege- mónicas occidentales. En su práctica, la artista considera la mercantilización no solo de la tierra sino también del cuerpo humano. Privatizar la tierra y politizar las fronteras tienen un efecto dañino sobre el medio ambiente, de la misma manera que mercantilizar el cuerpo humano —en el sistema carcelario migratorio, entre tantos otros sectores— tiene efectos tremendamente nocivos.

Aranibar-Fernández evoca los cuerpos de inmigrantes detenidos, refugiados y solicitantes de asilo mediante el uso de mantas de emergencia que cuelgan detrás del mapa en Desplazamiento y subsuelo. Estas mantas se distribuyen en los centros de detención del Servicio de Inmigración y Control de Aduanas (ICE) de EE. UU, que normalmente no tienen calefacción suficiente en invierno. Las imágenes de niños envueltos en estas mantas insuficientemente abrigadas que han circulado ampliamente en los medios de comunicación han expuesto las condiciones inhumanas de esos lugares. El uso de este material tiene la intención de recordarnos esos cuerpos, esos humanos, cuya sujeción actual a condiciones injustas es solo el horror más reciente en una larga historia de desplazamientos iniciada por el colonialismo y el imperialismo.

El cuerpo en movimiento es uno de los intereses de Cortés, quien trabajó gran parte de su vida como bailarina afrolatina. Hoy en día, su arte incorpora bordados cuidadosamente extraídos de los vestidos y chales que usaba hasta 2014, cuando un accidente de autobús terminó con su carrera de bailarina. En Cuna y La Cordobesa [figs. 6, 7], la artista adorna muebles antiguos con estos textiles, superponiendo sus significados originales con asociaciones híbridas que abordan la diversificación de las Américas. La cuna vacía hace referencia a la crisis humanitaria en la frontera sur, específicamente a los más de 5000 niñxs separadxs de sus padres desde julio de 2017.[2] Al cubrir la cuna con cuentas protectoras de vidrio y ornamentados con bordados florales que evocan al mundo natural explotado, Cortés destaca el complejo proyecto colonialista que ha dado forma a las Américas hasta nuestros días y, al mismo tiempo, conjura una energía protectora para lxs niñxs separados de sus hogares familiares.

Mientras que la obra de Cortés contiene prendas que ella solía vestir, Raúl De Nieves crea trajes elaborados, a los que suele dar vida a través de performances colaborativos de música y danza. Los conjuntos están densamente superpuestos con cuentas, plumas y lentejuelas. De Nieves se inspira en su herencia mexicana para usar abalorios. Sus disfraces y vidrieras de imitación están repletas de imágenes que aluden a las tradiciones mexicanas, a distintas religiones del mundo, a la mitología... Por ejemplo, las ranas en Coróname con tu hierro y ayúdame en mi lucha, en este y en todos mis días [fig. 8] simbolizan la fertilidad, la transformación y el crecimiento, que también son evocados por un embrión en el panel superior. Aquí, De Nieves explora temas de identidad y autorrealización a través de metáforas que hacen referencia a un proyecto continuo de transformación y sanación. Los significados fijos —como el crecimiento— de las imágenes en la ventana se vuelven móviles y subjetivos, a medida que espectadores con diferentes antecedentes y experiencias se encuentran con la obra. Es importante destacar que De Nieves superpone imágenes relacionadas para enriquecer y realzar su mensaje, que hablan de cómo crecemos a través del contacto con Ixs demás: un sentimiento especialmente profundo después de un año marcado por el aislamiento pandémico y las políticas xenófobas.

Los temas de la autodefinición, la narración y la herencia familiar también abundan en el trabajo de Ronny Quevedo. La práctica de Quevedo está directamente influenciada por las profesiones de sus padres. Su madre, costurera y modista, incluso le ha ayudado a crear varias obras de arte recientes, entre ellas topografía lyr(ic)a [fig. 9], En su elección de materiales —hilo, papel encerado y muselina—, alude al trabajo de su madre y al conocimiento heredado. Del mismo modo, su interés por los deportes, especialmente el fútbol, el baloncesto y el uIlamaIiztli (el juego de pelota precolombino considerado el antecedente de varios deportes de equipo contemporáneos) proviene de la influencia de su padre, que era jugador de fútbol profesional en Ecuador, y cuando la familia se mudó a los Estados Unidos, trabajó como árbitro y se unió a una liga de fútbol amateur. Las familias migrantes de América Central, del Sur y el Caribe conforman y coordinan estas ligas que se encuentran en todo Estados Unidos. La convocatoria semanal de estas personas, que a pesar de llegar de diferentes lugares comparten un idioma y la experiencia de intentar asimilarse a la vida en Estados Unidos, llegó a tener un significado ritual para Quevedo. Los equipos a menudo jugaban en espacios interiores, en canchas de baloncesto originalmente construidas para escuelas o grupos privados, lo que revela, para el artista, la forma en que los sitios pueden reutilizarse y reinventarse para cumplir nuevas funciones. A una edad temprana, Quevedo fue testigo de cómo su padre y su comunidad ingresaban a un espacio que no fue construido para ellos y escribían sus propias reglas para usarlo. Ahora, él ve esto como una metáfora de la inmigración, donde es posible celebrar la adaptabilidad y resistencia de aquellxs con gnosis inmigrante.

En el the killing floor (making ground) [fig. 10], Quevedo crea capas con referencias a deportes históricos y contemporáneos: reordena el piso de un gimnasio marcado con líneas de baloncesto para evocar la formación en 'I' de los campos utilizados para ullamaliztli. Traza líneas adicionales para desestabilizar aún más el vínculo entre este vocabulario visual y un deporte en particular. Las estructuras de metal colocadas en cada extremo recuerdan a los postes de la portería de fútbol o fútbol americano, pero aquí, en cambio, sirven para sostener sus dibujos en muselina. En la parte superior, las estructuras decagonales que evocan los aros de piedra que se usan en ullamaliztli están hechas de jabas de frascos de leche, como las que a menudo sirven como aros de baloncesto en el Bronx, donde Quevedo ha vivido desde que emigró de Ecuador.

La estética de Quevedo está determinada por su contexto actual, de la misma manera que la de Patrick Martínez. Martínez, que vive en Los Ángeles, adopta la pintura en aerosol, el borrado y las texturas toscas de los materiales urbanos para hacer un trabajo que recuerda el paisaje urbano y honra las historias contadas por las paredes. Esta práctica que celebra las superficies de su ciudad también evoca su historia y desarrollos culturales complejos. La yuxtaposición juega un papel importante en este cuerpo de trabajo, al igual que en el collage de letreros de neón creados para esta exposición. Aquí, Martínez agrupa diez obras de arte con citas, poemas y llamados a la acción, que invocan las palabras de Ixs activistas por los derechos migrantes y recuerdan a la audiencia que "la inmigración es natural", que "Estados Unidos es para los soñadores" y que "el odio es una carga demasiado grande de soportar" [fig. 11 ]. Martínez a menudo cita a personajes históricos que lucharon por la justicia social y racial; trae sus ¡deas y sentimientos al presente, y los junta con las luchas actuales en favor de la igualdad en esta nación. Estos letreros despliegan el lenguaje visual de la señalización comercial, un medio accesible, ubicuo y por lo general neutral, pero subvierten las expectativas al comunicar mensajes inequívocamente políticos.

En cada proyecto incluido en Comunidades Visibles: La Materialidad de la Migración, Ixs artistas utilizan referencias de fuentes históricas y contemporáneas, de diferentes partes del mundo y de diversas culturas. Lo hacen para construir un trabajo que habla de sus sensibilidades como creadorxs que están en un contacto consciente y profundo con sus gnosis inmigrantes. La hibridación de las obras de arte se interrelaciona estrechamente con las identidades híbridas de sus creadorxs: estas historias materiales, naturales y humanas están entrelazadas y son complejas. Honran a sus familias y a las historias que han dado forma a sus vidas, celebran y visibilizan las múltiples comunidades a las que pertenecen. Y, al hacerlo, exigen el reconocimiento del valor que poseen las comunidades de inmigrantes y las comunidades de color, basándose en el legado perdurable de los artistas y activistas que los precedieron. Sumo mi voz a estos llamados a la justicia, la equidad y el reconocimiento.

Al organizar esta exposición en un museo de arte reconocido internacionalmente, mi ambición era proporcionar una plataforma para amplificar las voces creativas de estos artistas. Mientras trabajaba en estrecha colaboración con cada artista en este proyecto, llegué a apreciar la complejidad de sus relaciones con este país y su herencia, que no es muy diferente a la mía. La experiencia encarnada de ser un inmigrante en EE.UU. da forma a nuestras percepciones sobre los eventos políticos y sociales recientes, también moldea nuestras respuestas frente a las injusticias (como el mencionado memorando del Censo), y también frente a nuestros procesos creativos. Fue a través del trabajo con este grupo de artistas que llegué a comprender exactamente cuánto tenemos en común como inmigrantes de primera y segunda generación, y cómo puedo utilizar mi papel como promotora de Ixs artistas y las personas latinas para aumentar nuestra visibilidad en nuestro (nuevo) país. post(s)

Referencias

Mignolo, W. (2012). Local histories/global designs: Coloniality, subaltern knowledges, and border thinking. Princeton University Press.

Notas

Información adicional

Cómo citar: Alvarez, A.

(2021). Immigrant Gnosis: Hacer obra en los Estados Unidos. En post(s), volumen 7 (pp. 180-207). Quito: USFQ PRESS.